snotknot's security thread (part 2)

Introduction

Welcome to part II of my security thread. I’m unfortunately pretty late to the party in terms of my planned release date for part II. Summer of 2022 was the plan. It’s half way through April of 2023 when writing this.

In part I, I introduced you to a thread that was created by a silk road user back in 2014. I hope that you were able to realize the age of that thread. Some things were out of date. Most of that thread is fortunately still relevant today which is why I included it as a resource despite its old age. Upon writing part I, I initially planned on copy/pasting sections of that thread and then “updating” it with todays relevant information. I soon scratched that idea as I realized that most readers would have the common sense to know what information they should or shouldn’t trust in terms of how “relevant” the information is today. If you read a thread written in 2014 that says “this type of RAM is popular!”, I expect you to have the brain capacity to realize that may not apply today due to hardware changes.

Within this thread, we will continue to discuss more important things relating to security, privacy, anonymity, OPSEC, and so on. This isn’t just a “security” thread if that wasn’t made apparent already. It’s important to learn what and why before learning how. I encourage that you do not skip along as it may one day come back to haunt you when you’re not knowledgeable about a particular subject. Let’s say hypothetically that you’re doing something illegal on your computer. Your computer is encrypted but you leave your computer powered on and locked overnight. Do you see any issues with this? It’s okay if you don’t as we’ll be covering this in detail throughout the thread (spoiler: RAM attacks). You also didn’t pay that close of attention to the Jolly Roger thread as he covered on this topic. If you were to skip along, it’s possible that you may have missed the part in the Jolly Roger’s thread where he covers why this isn’t such a good idea. That one mistake may have you arrested as police have access to a live unencrypted system. Reading the thread would have likely prevented you from making this mistake. This is why you should read everything and in order. Knowledge is power, literally.

I will reiterate from part I: I do NOT support or condone illegal activies. Illegal activities are used as a base example to help demonstrate points for various reasons. That doesn’t mean illegal activities are encouraged. In fact, you won’t learn how to do anything illegal reading these threads.

What data does your ISP collect about you?

Your ISP (Internet Service Provider) is the company responsible for providing your internet connection. Registration with an ISP requires personally identifiable information. This should come as no surprise as you have to pay for this service with your personal credit card and provide your address for installation.

You’re instantly providing your ISP with your personal information, and will continue to provide them your data as you use their service. What exactly is this data?

Whenever you make a connection over the internet, your ISP will log the IP address, domain & subdomains that you made the connction to, as well as the date and times that the connections were made to said IP addresses/domains. For example, your ISP knows that you connected to google.com at 4:00pm last Thursday. Your ISP can’t see the contents of your session (the data you’re sending and receiving), they can only see smaller pieces of metadata. However, your ISP can see the contents from connections that are not encrypted.

If you’re accessing a website that utilizes HTTPS (the vast majority of websites nowadays), then the data logged by your ISP will be limited as it’s an encrypted session. However, if you’re establishing an unencrypted session such as a websever running over HTTP (not encrypted), for example, then your ISP will be able to see everything going on during that session including the contents exhanged between you and the web server.

Another thing that’s useful to know is if you’re using HTTP, your ISP can see the entirety of the URL instead of just the IP/domain/subdomain like they would if you used HTTPS. For example, if Google didn’t use HTTPS, your ISP would be able to collect every search query you make on Google as Google appends your search query into the URL. For example, if you search “example123” on Google, the URL will look something like:

https://www.google.com/search?q=example123&oq=example123&aqs=chrome..69i57.2598j0j1&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

Your ISP would log the entirety of this URL instead of just “google.com” if Google was running over HTTP.

Thankfully this isn’t the case as Google utilizes the HTTPS protocol which offers end-to-end encryption to our session. This means the data flow is encrypted from the second it leaves the browser, all the way until it reaches the web server, which prevents our ISP from logging the contents as they’re not able to read our contents in the first place due to it being encrypted. Yay!!! Or is that something we should celebrate? Does this solve the whole data collection problem? Is encryption the savior we all need? Yes and no. It reduces the problem more than it solves it. The encryption only stops unauthorized people from snooping on the data flow to see what we’re up to. Google can still see exactly what we’re doing in plaintext as they own the encryption keys to decrypt our requests.

The point to take away here is to not think your ISP doesn’t collect the contents of your session because they “respect your privacy”. This is not true. The only reason they don’t collect the contents of your browsing sessions is because they’re unable to majority of the time. Many online services utilize encryption. This will prevent your ISP from logging the contents of most of your online sessions. If you establish a non-encrypted session to a server, your ISP will log everything including the contents of your session as it will not be encrypted. For example, if you download an image over HTTP or some other unencrypted network protocol, your ISP can retrieve that image just as anyone could who is snooping your traffic. Even if you simply view the image in your web browser without downloading it locally to disk, your browser still had to request that data from the server for it to load in your browser. These actions are made in the form of “HTTP requests”, and these too are logged as it’s part of the unencrypted data flow.

These are the main things you need to know about in terms of what data your ISP will collect on you. There’s other things I didn’t mention but they’re common sense when you think about them. For example, your ISP is also able to tell how long you’re on a particular website. This is due to the fact that all of your data will route through your ISP before it reaches the server you’re connecting to. Your ISP is the message man who is forwarding all of your data as well as sending it back to you.

The full comprehensive list of the data collected by your ISP will differ depending on the network protocols that were used throughout your internet activities. Some network protocols utilize encryption while others don’t, and some protocols may collect data that others don’t. A good rule of thumb that applies to all situations, however, is everything will be logged for unencrypted connections while less important metadata will be collected for encrypted sessions.

Data collection exists for many reasons: data sells well, and for bulk collection (“AKA the goverment’s euphemism for mass surveillance”. ~ Edward Snowden)

The truth about VPNs

If you haven’t been living under a rock recently then you definitely have had VPN advertisements shoved in your face while browsing social media. These are more common on YouTube as VPN providers will pay bigger YouTube channels to advertise their product. These advertisements will sometimes be misleading as the VPN providers may write nonsense on the script they’re paying the YouTuber to read aloud to the camera. This causes a lot of people to be lied to about the capabilities of VPNs.

I want to make it abundantly clear that I have nothing against public figures who accept sponsorship deals with VPN providers. Most probably don’t know better and simply read the script. YouTube also demonetizes creators, so I understand why people would accept these offers. It’s perfectly acceptable to lack the knowledge of VPNs. I believe that most people who accept these sponsorship deals are not intentionally spreading misinformation. The problem is not the creators accepting the sponsorship deals. The problem is when VPN providers intentionally spread misinformation for marketing reasons so that they can cash out on the profits.

VPNs are good for:

- security (they offer an additional layer of encryption, so if you happen to establish an unencrypted session (HTTP, open Wi-Fi, etc.), it’ll prevent the data from being accessible to anyone trying to perform MITM attacks on your traffic flow including the ISP or the network you’re on, however the VPN server you’re connected to will obviously be able to see everything)

- bypassing certain types of censorship (pirating content without your ISP calling you and complaining, geographical restrictions (i.e., media that’s only available in certain countries), IP bans, IP-based rate limiting, etc.)

- getting a new IP address

VPNs are not good for:

- privacy (with VERY small exception)

- anonymity

The very niche situations where VPNs are “good for privacy”

You’re probably spinning in your chair confused saying to yourself “why did this idiot say VPN’s aren’t good for privacy, meanwhile the next section is “why VPN’s are good for privacy””. There are 100x more reasons why VPNs are absolutely awful for privacy than why they’re good for privacy. This is why privacy is included as one of the things VPNs are not good for.

I guess the only privacy advantage VPNs offer is their capability to mask your IP address to prevent your real IP address from being logged on servers that you don’t trust or know the owner of. This could potentially be a privacy concern to some. Someone with your IP address can figure out what ISP you use, the country you live in as well as your precise city (and in some situations your IP will lead to your exact city). This is all publicly available information that anyone can obtain if they have your IP address. There are many freely available resources online such as iplocation.net which will tell you all of this information of any IP address you enter. Some consider this vital information that they don’t want anyone obtaining. If this is the case for you, then a VPN is a great choice. The vast majority of people do not care about the metadata tied to their IP address. “Oh no, somebody online knows I live in Los Angeles and use Comcast!!!”. VPNs also help mitigate DDoS attacks as the attacker won’t have your real IP address to flood with their botnet, but your VPN IP address instead. It’s also never fun when some cringy 16 year old kid with a subscription to a booter is nonstop hitting you offline because they have nothing else better to be doing.

Another advantage of a malicious actor not having your real IP address is the capability to use it to discover internet-facing devices on your network. This doesn’t include devices on your network that are connected to the internet, but rather devices on your network that have services running on them with ports open to the internet that can be remotely connected to from anywhere in the world (outside of your LAN). Every network is different, but an example may include an IOT device that comes built in with a web interface designed to be remotely accessible to administrators. This is common with many IP cameras.

This is more of a security problem than a privacy problem as a VPN prevents anyone from obtaining your real IP to scan your network, potentially compromising a public facing device. It doesn’t make your privacy any better, (the potential private data stored on said scannable systems open to the internet) because if you lack the appropriate security knowledge to where you’re incapable of securing an internet facing system from attackers, then a VPN isn’t going to be the magic bullet that saves the day.

A VPN may benefit you in one or more of these situations, but it’s important to note that the majority of people do not care about most of what was mentioned. We may over analyze these factors as security minded individuals. Most don’t.

Why VPNs are not good for privacy

The big problem today is the issue we have with the bulk collection of data. As we already discussed, our ISP is no exception to this problem as they log a lot of information about our internet activity.

When you’re using a VPN, your VPN provider essentially becomes your ISP. You’re shifting all of your trust into your VPN provider, and you’re providing your VPN provider with all of the information that you were once providing your ISP. When you’re using a VPN, the only thing that your ISP can see is that you’re sending and receiving encrypted data to a VPN server IP address (and remember, your ISP can see that the server belongs to a VPN due to the public information tied to IP addresses).

VPNs do not solve the issue of data collection as many VPNs also collect your data similar to your ISP.

What many people don’t know is that VPN’s are legally allowed to lie about their data collection habits. Many VPN providers will claim they do not keep logs of your activities for marketing reasons when they likely do. There’s been many instances where big name VPN providers were caught red handed keeping logs of their users. These logs were then handed off to law enforcement after they subpoenaed the VPN provider for user logs.

Remember on Christmas day of 2014 when the Playstation Network servers were hit offline from a DDoS attack? The hacking group responsible for that attack was Lulzsec. I was playing Far Cry 4 on my PS4 that I just got for Christmas. Jokes on you Lulzsec; I was playing the campaign, I didn’t need to access the Playstation servers. One of the members of Lulzec used a VPN provider called “HideMyAss”. The FBI subpoenaed the VPN provider who claimed to not keep user logs and it lead to the arrest of the member as he didn’t have a good OpSec foundation and relied solely on a VPN. If you’re interested, you can read more about one of the members getting caught in a similar story here.

Many big name VPN providers were caught red handed keeping user logs despite claiming they don’t meanwhile they are still performing strong in the VPN industry. Why do you think people continue to use and support these VPN providers even after all of the evidence of them keeping your logs? Why do you think stories such as the one linked above didn’t blow up in the media as much as it probably should have? Probably because VPNs aren’t as good for privacy as you think. Perhaps there’s bigger and better reasons to use VPNs?

Despite all of the evidence, you also have to use a little bit of common sense. Why would VPN providers NOT log your data? Data is so valuable in todays world that they would be losing out on a lot of potential profit if they chose to opt out of data collection entirely as most claim to do. What if you’re using a VPN who offers cheaper subscriptions than their competitors? How do you think they’re making up for that profit? They are probably selling your data. Data collection is even more likely with cheaper VPNs.

So many people blindly establish trust foundations with these VPN providers without any valid reasoning. They’re a business, they want to make money. Your data makes that very easy. Are you correct when you say VPN provider “X” doesn’t keep logs? You may be, but “may” isn’t a good enough answer if you’re wanting genuine privacy. If you have to question your privacy, then you have none.

Data Retention Laws

Data retention laws is one of the most common counter arguments that I see online with people defending VPNs as if they are the saint of the planet. Don’t get me wrong, I myself use a VPN (sometimes) and heavily encourage you to do the same. However, a VPN is a VPN. VPNs are not magic.

Certain countries have data retention laws that require VPN providers to retain certain types of data for a certain period of time. For example, if you operate a VPN provider in the U.S., you will be required legally by the U.S. government to retain logs of certain types of data for a certain timeframe. This means that if NordVPN, for example, operated out of the U.S. and then claimed to not keep any logs, they wouldn’t be believable as they would be legally required by the government they operate out of to do otherwise.

This is why you see many big name VPN providers operate out of countries such as Switzerland or Panama as these countries do not have required data retention laws that you must abide by if you operate a VPN provider. I’ll use NordVPN as an example. NordVPN claims to not keep logs and operate out of Panama. This makes their claims of not keeping logs more believable.

Do these VPN’s ACTUALLY log your data? Are they lying? We will never know. The only people who know for sure are the higher ups at these VPN’s. What we do now however, is that it’s stupid to blindly trust claims without valid reasoning. “Trust us that we don’t keep your logs because we aren’t legally required to!” isn’t a good reason.

Some VPNs may not be LEGALLY required to keep your logs, but who says they’re not deciding to keep your logs on their own terms despite if they’re legally required to or not? We already know that data sells well. Why would they lose out on that profit when they can simply claim they don’t keep your logs to attract even more customers and then sell it on the side anyway for extra profit? Claiming to not keep logs = more customers = more data to sell = win win for VPN Provider, as well as happy customers who “think” they have privacy.

Conundrum land: “What do I do?!”

Many people opt into using a VPN as appose to routing their traffic directly through their ISP due to the fact that their ISP will certainly log their data, whereas their VPN may or may not. They weigh the risks and go down the VPN route as it’s the safer option of the two. This may make sense for your average person who only slightly cares about privacy or for someone who doesn’t want to allocate a bunch of time and effort into it. However, for someone who deeply cares about privacy, this isn’t the best decision.

We shouldn’t have to be placed in a situation where we have to fucking roll the dice and calculate risk management to determine which one of our limited options is the best outcome for our privacy. This is the EXACT issue that we have with online privacy; imprecise solutions that don’t guarantee an outcome in which gullible people trust.

You may be asking yourself, “So then what’s the solution? I either give my data to my ISP, or I blindly trust a VPN?”.

When it comes to security, privacy, anonymity, etc., there is ALWAYS a solution. There’s always a way to overcome the problem and regain control and it will always be like that for the entirety of time. Some are harder than others and some may or may not be legal, but the point still stands; there is always a way to overcome the issue, even if the solution is to stop using the internet entirely. It just depends on how much you care and how much effort you’re willing to put into it to “win” the battle.

The solution: Creating your own VPN

If you do seriously care about your data potentially being logged as it’s in transit to its destination, there thankfully are ways for you to regain control. The solution is to create your own VPN. The idea behind creating your own privately controlled and hosted VPN is so that you have full, physical control over the server powering it and can guarantee that your data is in safe hands and isn’t being logged.

Creating a VPN is extremely easy to do. This is a common misconception to many as most people think of the big name VPN providers when they hear the word “VPN”. They are big companies, what they’re doing must be complex, right? Not so much. To make a VPN provider with thousands of servers that millions of people use is a very hard task indeed. However, you’re one person. You only need a server that can handle your traffic flow, nobody else.

The only tricky part to creating your own VPN is the hosting. Are you going to host it at home off a Raspberry Pi? Are you going to turn a shitty PC from 2008 that you have in your closet into a VPN? Are you going to rent a cheap VPS and turn it into a VPN? It’s entirely up to you and any method of hosting will work depending on your situation. Each method will have pros and cons. One of the caveats you need to be aware of is that whatever network the VPN will be hosted on will be the VPN’s public IP address. For example, if you host your VPN at home on your own hardware, your VPN will be using the same IP address assigned to you by your ISP. If you host a VPN in the cloud, that cloud servers IP address will be your IP address when connected to the VPN. The VPN will not magically spit out a random IP address different from the IP of the network it’s running on. That obviously wouldn’t make sense. A VPN’s job is to provide an encryption tunnel for your data flow to go into. Changing your IP address will only be a perk you can leverage if the VPN is hosted on a separate network different from your own.

Home hosted VPN’s unfortunately will not allow us to reap the benefits of having a new IP address (bypassing IP bans, etc.).

If you host your VPN with third party paid hosting, you essentially have a “dedicated” IP. You just have to be careful to not burn this IP, as you cannot simply switch to another VPN server like you would be able to with a big name VPN subscription.

If you use third party server hosting to host your VPN, you have to also consider the privacy policies of that provider. They too will hypothetically become your ISP just as your traditional paid VPN would because your network traffic will be routed to their server that you’re renting. They too will be able to see your network traffic in plain text (they own the server you’re renting therefore they have access to the contents stored on it). Are you doing anything illegal/weird/sketchy? If so, is that provider able to be subpoenaed? Even if they claim they cannot, do you really trust that they can’t? Do you think they’re going to say no to the feds and risk getting shut down or sued over a $15/month subscriber?

It’s bad OpSec regardless of the context to route your network traffic tied to your illegal activities to a server that you pay for with your real identity or if it can identify you (including your ISP). Even if you’re not doing anything illegal and going Edward Snowden mode leaking NSA documents, do you care if the provider can read your network traffic? If not, then at that point just use a regular VPN or don’t use one at all. At the end of the day, SOMEBODY will be able to read your network traffic unless if you have 100% full physical control over your private VPN. This means there’s no middle man that you’re relying on for the uptime of your server (i.e., a hosting provider). This will ensure that the only people who can read your traffic will be the owners of the servers you connect to, there’s no preventing this other than to simply not connect to that server. You won’t be able to prevent the owners of the servers you connect to from seeing your contents as they own the encryption keys to their own servers to decrypt your requests.

… or CAN YOU PREVENT them from seeing your contents?

Remember how I said there’s always a solution? What if you take the power of encryption back into your own hands and encrypt your own sensitive data? For example, what if you encrypt the contents of your emails with PGP while using Gmail? This will prevent Google from accessing your email contents. Granted they will still log the email contents in which you encrypted, but they won’t be able to read it… because it’s encrypted.

The Money Shot (Conclusion)

I know this entire VPN section has been a rollercoaster thus far. The reason I went off on a tangent is due to the fact that there isn’t a simple “yes” or “no” answer to VPN’s. It depends entirely on your needs.

Somebody who doesn’t want their network traffic monitored whether if they’re participating in sketchy activities or if they are a privacy enthusiast will need to take extra steps to accomodate their needs. In contrast, if you’re an average Joe who isn’t doing anything sketchy and if you don’t care about your privacy, then who the fuck cares? Use a VPN or don’t. Use a shitty VPN or use a good VPN. Are you doing anything illegal online and your threat model is the government/law enforcement (which they will be)? Then you shouldn’t be using a VPN regardless.

Bonus Section: The technical details of how a VPN works

I tried my best to keep it relatively to the point in the sections above, however now we will dive deep into the details of how VPNs actually work under the hood in terms of encryption and how that ultimately benefits/damages our privacy, security, or anonymity. This is a prime example of where the prerequisites of these threads that were listed in Part I will become important. We will be covering topics relating to cryptography, networking, and basic intermediate-level topics on information security and how information systems function.

I mentioned previously that VPNs have one job; act as a man-in-the-middle proxy that encrypts your traffic flow to and from its destination. How do VPNs accomplish this? Why is this a good idea? Is it useful?

VPN servers will use a variety of different communication protocols that work in conjuction with networking protocols to encrypt and route your traffic. The most popular communication protocols that VPNs will use are Wireguard and OpenVPN. Wireguard is newer and faster than OpenVPN and is used mainly by VPN clients that are used in Windows environments. OpenVPN, although older and slower, have been around for long enough to the point where there’s a lot of support behind it and is fast enough for most use cases. OpenVPN is also supported by a large number of VPNs and is used a lot in Linux environments.

The Cryptography

The most important part of a VPN is the encryption, or is it? Does it really matter?

The encryption aspect of VPN’s are great for if you’re on an open Wi-Fi network and don’t want your traffic being intercepted granting anyone the power to see what websites you’re visiting. If you establish an unencrypted session, anyone intercepting your traffic (ISP, someone intercepting your traffic via MITM attacks, etc.) will be able to see the contents of your session. If you’re using the open Wi-Fi of your local coffee shop and establish an unencrypted session to a webserver and download an image without a VPN, then the creepy guy sitting next to you intercepting packets in Wireshark will be able to see the contents of your session including the image you downloaded. A VPN would prevent these types of MITM attacks as it will use end-to-end encryption to encrypt that session. This would result in the person intercepting your traffic to simply see encrypted traffic that they can’t do anything with. If you want to know what it looks like to intercept encrypted VPN traffic, then connect to a VPN and capture packets locally on your system using Wireshark. You’ll see a bunch of encrypted traffic belonging to Wireguard/OpenVPN/whatever protocol your VPN uses.

The “hackers stealing your information while you’re online shopping” is the scenario a lot of VPN’s use in their advertisements to help sell their product. This isn’t going to be true 99% of the time as all well known and reputable e-commerce websites/applications these days will utilize end-to-end encryption, rendering this claim as false. In fact, I can guarantee that there isn’t a single reputable online banking/online shopping website/app that doesn’t use end-to-end encryption for their service.

Let’s pretend for a second that the “hackers stealing your data while you’re online shopping” hypothetical were to be true. Even if you’re connected to an open Wi-Fi network at a coffee shop without a VPN, someone intercepting your traffic isn’t going to be able to access any juicy information from your Amazon session as if they’re playing Watchdogs or performing a hack straight from a movie. This isn’t 2007 and you can’t just “capture passwords”, or anything useful for that matter, over the wire using Wireshark or a similar packet capture application.

Once again, this is due to the fact that your session will be utilizing end-to-end encryption. Let’s say you’re shopping on Amazon.com while using open Wi-Fi without a VPN. Amazon’s website runs over the HTTPS protocol, which will use the TLS cryptography protocol to encrypt your traffic flow. Your session will be encrypted regardless if you’re using a VPN or not. A VPN will simply add an additional layer of encryption.

There are some people who believe that using a VPN is a great advantage for all people as they offer an additional layer of encryption to your network traffic. This is definitely true, a VPN does indeed add an additional layer of encryption on top of your (mostly) encrypted network traffic. However, due to the fact that your online sessions will already be using modern day cryptography to protect your sessions, it would be redundant to use a VPN as an “extra layer” of encryption. You already have an encrypted layer that isn’t going to be cracked. The VPN does nothing. Nesting encryption would be useful for something such as encrypting drives with extremely sensitive data on it, not for VPNs.

The only time this claim will be true is when you establish an unencrypted session to a server. As we already discussed, the VPN will wrap that once unencrypted session in an encrypted tunnel for you. However, most people aren’t establishing unencrypted sessions these days, and even if they are, there is probably a reason as to why that server isn’t utilizing encryption… It probably doesn’t have a reason to as there’s nothing sensitive being transmitted within that session.

Think about it, how often are you visiting sketchy random ass websites running over HTTP that ask for sensitive information that you then give to that website willingly? Let’s say hypothetically that you do give this website your information. What are the chances that somebody will be simultaneously performing a MITM attack by capturing packets locally on your network, an attack in which they ALSO NEED ACCESS to the Wi-Fi network you’re using, BTW. Next to zero.

Let’s pretend that you DO hypothetically provide a website that belongs to a scam, for example, with your personal information. Well, regardless if that website is running over HTTP or HTTPS, your personal information will still be in the hands of the scammer regardless if the session was encrypted or not, if you used a VPN or didn’t, and so on. None of it matters. There’s no VPN or encryption that will prevent them from retrieving your personal data that you gave their server. You should hopefully know why by now, but the answer is because they own the webserver that you gave your information to therefore they own the keys to decrypt your data (if encrypted).

VPN’s, the websites you visit running over HTTPS (almost all websites), and all of the other encrypted services you connect to and use every single day whether it be on your computer or phone, etc. are almost all going to be using modern encryption for todays standards that follow kerckhoff’s principle. Kerckhoff’s principle means that the encryption will be so strong that not a single person or thing can crack it/overcome it, even if they know everything about the encryption algorith except for the key (obviously).

That means that if you, for example, encrypt a flash drive using an encryption protocol that follows kerckhoff’s principle, nobody and nothing, even the police or the government, can access the encrypted contents unless if they somehow obtain the private encryption key containing the instructions to decrypt the data. This will typically be in the form of a user supplied password and the encryption will be derived from said password. They can surely try to find a way AROUND the encryption by cracking the password using various password cracking methods, but as long as you have a strong password then it will take hundreds or thousands or even millions of years to crack that password. This may not be so true years from now when we have quantum computing but regardless, that’s not true as of today. Technology also advances with time, meaning that a better solution will be created even when we do have quantum computing.

Think of modern encryption as an indestructible wall that cannot under any circumstances be destroyed, similar to Bedrock from Minecraft. You can try to dig a whole underneath the wall, climb over it, or simply walk around it… but you can’t break it. This is the perfect euphemism for modern day encryption that follows Kerckhoff’s principle. The FBI may try their best to find a workaround by attempting to find the encryption key; the password of the encrypted flash drive, but they can’t just “remove” the encryption without losing the encrypted data.

Apple vs. FBI

Remember in 2015 when the FBI tried to subpoena Apple for the contents stored on one of the phones belonging to one of the San Bernardino shooters? Apple told the FBI to fuck off as even they cannot decrypt the contents stored on their phones (locally, they can still decrypt what’s in your iCloud and so forth). This is because iPhones use encryption that is derived from the password that YOU as the end user supply, therefore you’re the only person with the key. It would certainly be a whole hell of a lot easier to bruteforce the password of a mobile device as most people use very weak 4 digit pins as their password. This would be relatively easy to crack as there can only be 10000 different combinations. Nowadays we have biometrics that can assist in unlocking our phone. I believe biometric data can be subpoana’d in the U.S. for investigations, do not quote me on that.

“Why didn’t the FBI just bruteforce the 10000 different potential combinations???”

The problem with that technique is that most mobile devices will have a limit on how many password attempts you have until the device hard wipes itself or gives you a time in which you’ll need to wait out (often times both). The FBI could often times crack these 4 digit passwords with older versions of iOS until Apple made an update to wipe the device after a certain amount of incorrect attempts. The FBI also compelled Apple to build a backdoor to bypass the security features of iPhones, in which Tim Cook told the FBI to go fuck themselves.

If you want to learn more about how the FBI accessed the data on the phone, you can read more about that here.

Back to VPN’s. We already know that Wireguard is one of the more common protocols used by VPN’s. Wireguard will encrypt the data using the ChaCha20 cipher and send the traffic via the UDP internet protocol. What is UDP and why UDP?

TCP & UDP

Networking knowledge was one of the listed prerequisites for these threads, but let’s be honest… most people probably skipped the prereqs. I am going to explain TCP and UDP as it is very important to know. If you are going to be working in IT, many jobs (except for maybe entry level jobs) will not hire you if you don’t know this basic knowledge and it is crucial to know how your online sessions are established. What happens over the wire when you connect to google.com?

UDP, or “User Datagram Protocol” is one of the two most commonly seen internet protocols, with the other being TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), that are used in conjunction with other protocols such as but not limited to HTTP or HTTPS. TCP is a slower, yet more reliable protocol and is considered a connection-based protocol.

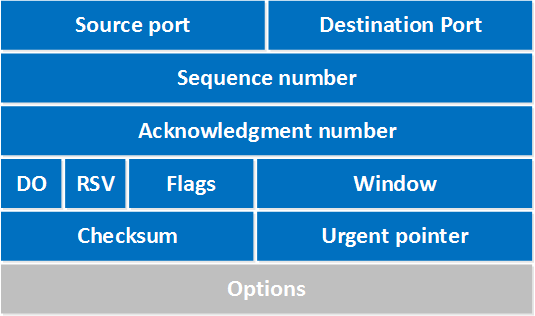

Connection-based protocols will have a dedicated procedure for establishing a session, which is establishing a handshake between the server and client. This “handshake” will be a preliminary, pre-agreed on set of instructions that act as an agreement with information regarding the session and how it will take place. The client will send a packet to the server requesting to establish a connection. This is known in the TCP three-way-handshake as the “SYN” packet. “SYN” is short for synchronize. The server will then respond to the request made from the client with a “SYN/ACK” packet. “SYN/ACK” is short for synchronize acknowledge, which is the server acknowledging the synchronize packet from the client. Finally, the client will send another SYN packet to the server acknowledging the SYN/ACK packet from the server. The three way handshake will finally look like this: (Client) SYN > (Server) SYN/ACK > (Client) ACK.

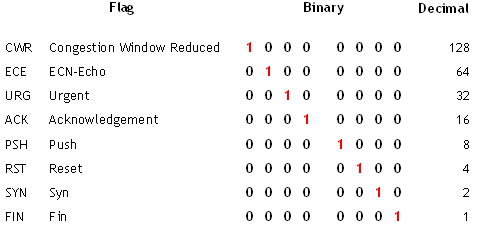

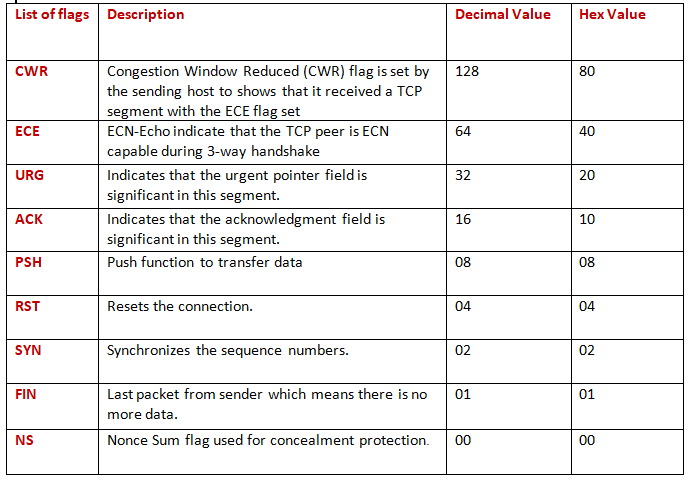

The way these packets are defined are by the packet headers of the TCP protocol. One of the headers will be reserved for flags, as shown below:

The various flags:

Flag descriptions:

These flags are binary based, and the bit responsible for the appropriate flag will be set to “1” to represent “true” or that bit being “turned on”. For example, a SYN packet will have the value of “1” for the SYN flag. When this packet arrives at the server, the server will strip down the packet and ultimately analyze the flags in the headers, realizing the bit responsible for the “SYN” flag is set to 1. This is how the server will know the client is trying to establish a connection, because that’s what the SYN flag means. The rest of the process is pretty straightforward: the server then responds with the “SYN/ACK” bit set to “1” in the header’s flags, then the client responds with another packet with the “SYN” bit set to “1” in the header’s flags. The connection is finally established and the client/server are ready to start sending data.

TCP has other built-in features that are convenient depending on how the protocol is being used. The most notable feature of TCP is the error-checking capabilities built into the protocol. This will, for example, prevent a file you’re downloading from having missing chunks if your internet is spotty or if you ultimately end up losing connection for a brief second during the download. This is not possible with TCP. TCP will hash the sum of the data you’re trying to download before the download begins, then hash the sum of the data once again when it arrives at the destination (when the download is finished). If even 1 bit is changed, the hash value will be completely different, telling TCP that you don’t have a bit-by-bit copy of the original file you’re downloading. If this happens, TCP will reconstruct the data stream with the range or “offset” of bytes missing from the download to ensure that you got all of the data in its entirety.

Not only does TCP hash the contents when they arrive at their destination for data integrity purposes, but TCP will also detect lost packets in real time, make a note of them, and then put them into a list of packets that need to be made up or “re-sent”. Think of it as if the missing packets are being placed in order onto a conveyor belt for retransmission.

TCP is great for file downloading, emails, or browsing the internet, but imagine how hectic it would be if TCP was used for online gaming or video calls. If there was even the slightest bit of lag in your connection, then your online game/video call would become delayed and even more delayed as the packets that were lost during the lag have to be reconstructed and retransmitted to you. This is where connectionless protocols come into play.

In contrast to a connection-oriented protocol such as TCP, we have a connectionless protocol known as UDP. Connectionless protocols are able to establish sessions between a client and server without a prelimary agreement or “handshake”. Connectionless protocols such as UDP are also not strict when it comes to packetloss. If you have packetloss during data transmission with UDP, UDP will not make note of it and correct it like TCP will, UDP will simply move on. This is the perfect alternative to the TCP related issues we had with online gaming or video calls. If you’re playing an online game and you have packetloss due to spotty internet, your computer and the server won’t have to play catch up and attempt to re-send the lost packets. Connectionless protocols such as UDP are why player character models will teleport on your screen. There’s packetloss somewhere in the mix… maybe on your end, the other player’s end, or the server. If the online gaming server was using TCP, then you would see the player character model retrase its steps as it makes up the packets lost in transmission. It would look similar to a video being sped up. Either that or the player character model will permanently be delayed as it’s making up the lost packets AND sending/receiving up to date packets in real time. More packetloss = more delay. Think of it as if the conveyor belt is constantly being fed more packets onto the end than it can keep up with.

Back on track

We’re back on track now: why VPNs will use UDP. Sorry to hit you with that TCP/UDP side quest. It’s important to know for VPNs (or for anything for that matter, as either TCP or UDP will be used for the vast majority of your sessions).

It’s obvious that VPNs primarily use UDP now that we know the difference between the two protocols. All of your internet traffic, which will consist of a mix of traffic transmissions using both UDP & TCP, will be tunneled to your VPN. TCP would be a nightmare, especially for UDP traffic. Many VPNs will attempt establishing a connection over UDP, and then resort to TCP if UDP fails. This is a result of some TCP ports being blocked on certain networks, where maybe a network administrator is showing strict principle of least privilege restraint and only whitelisting the ports necessary. OpenVPN by default will establish TCP connections on port 443; the default HTTPS port. 443 is almost never blocked as it’s required for web traffic.

Once the connection is established to the VPN, your traffic flow will then be routed to the VPN server in an encrypted format. That’s it. That’s all a VPN does, Tadaaaaaaaaaaaa.

Were you expecting more?

VPN + Tor = bad

TLDR: Do not combine a VPN with Tor for anonymity, but rather convenience purposes. VPN’s do not offer anonymity. Combining a VPN with Tor, something that does offer anonymity, is useless.

There are a few reasons why someone may want to combine Tor with a VPN that they’ve purchased anonymously. They do this not for anonymity, but for convenience reasons. There are people who “think” they’re using a VPN for anonymity… they’re not.

If you’re accessing the clearnet, having a VPN as your end node (You > Tor > VPN) rather than a tor exit node (You > Tor, or You > VPN > Tor) will often times be a lifesaver since websites can tell that you’re using Tor.

Tor relay IP addresses are public information on the internet. This allows services that you connect to (such as Google, for example) to know that you’re using Tor if you have Tor as your exit node. Google will see that you’re using Tor, and will assume that you’re a bot who’s up to no good and put you in endless captcha land. This is because people abuse the Tor network for nefarious reasons, which in return forces services to blacklist and/or rate limit Tor connections. This can be really annoying if you’re an innocent person who’s trying to simply browse Google without being bothered by captchas. These are all reasons as to why it may be convenient to have a VPN as your end node, assuming the VPN IP also isn’t IP-banned/rate-limited, obviously.

I recommend watching a video made by a prior Darknet vendor/hacker who sold moonshine on the dark web. He often gives OpSec lessons on his YouTube channel and most of his journey is documented not only on his personal channel, but his Defcon conference.

No Logs VPNs fail for Darknet OpSec - Deep Dot Darknet: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6arTTIcE4LA

Tor: Darknet OpSec By a Veteran Darknet Vendor & the Hackers Mentality (Defcon 30): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NGiUhjuB22Y&t

He goes into detail on why it’s not really a good idea to combine a VPN with Tor when your threat model is the government trying to arrest you. His OpSec was so incredible that the feds had to break the law to catch him. He never used a VPN. How did he do it? By not being complacent and understanding each layer of his OpSec foundation. Him using a VPN would not have increased his anonymity or OpSec foundation at all. The Defcon conference isn’t really about VPN’s but more of an interesting watch if you’re into OpSec.

If you want to go full out paranoid mode and use a VPN “anonymously”, then the correct method would be to use crypto in which you’ve also obtained anonymously, VERY important (don’t be that guy who uses Coinbase to get your crypto), to anonymously purchase a VPN subscription that you will connect to ONLY over Tor with a torified OS such as Tails.

The connection chain will look something like this: You on a Wi-Fi network that you don’t own and doesn’t identify you personally > Tor (with bridges) > VPN paid anonymously with crypto.

The reason why you need to acquire this VPN subscription anonymously should be very obvious, but I will cover it anyway: If you’re going through all of these hoops to build your anonymity foundation, and then use a VPN that you pay for with your real identity… you’re not very “anonymous”, are you?

Even when connecting to a VPN over Tor that you’ve payed for anonymously, you have to ask “Am I gaining a genuine anonymity advantage?”.

That’s a legitimate question. Are you? You’re connected to that VPN anonymously, but is that VPN granting you additional anonymity, or is it just one extra unnecessary layer in your OpSec foundation?

It’s just one extra hop that your traffic has to go through. What would be the difference if you just had Tor as your exit node?

READ: “Tor + VPN = Bad (Continued)”:

https://snotknot.github.io/blog/Tor+VPN

I have a newer blog where I go more into detail on why it is a bad idea to combine a VPN with Tor.

Exit node de-anonymization attacks

Let’s debunk a common argument many people, including you, may have as to why you should combine a VPN with Tor.

“What about goverments who create Tor exit nodes to perform de-anonymization attacks on Tor users?”

If you didn’t know, anyone can create a Tor relay. Tor relays are created and maintained by voluntary members of the community. Anyone can create a Tor entry node, relay node, or exit node… including your government.

With cryptography, the exit node, which is the last node in the connection chain, is the node responsible for decrypting requests. However, when you establish an end-to-end encrypted session to a server, that server then becomes your “exit node”, and that server will be responsible for decrypting your requests.

The idea behind the de-anonymization attack argument is that if you happen to acquire a Tor circuit (what makes up your three nodes; entry, relay, & exit), and if your exit node happens to belong to Law Enforcement or the government, then they will be able to decrypt your requests since they own your exit node.

However… remember how I said that the server becomes your exit node when you’re connected to a server that utilizes end-to-end encryption? Well, .onion sites offer end-to-end encryption.

This means that even if you do have an exit node in which is ran by the government/police, they will not be able to access the contents of your session as it will be encrypted, and the .onion site is the one performing all the decrypting power. However, any unencrypted traffic will be in the hands of whoever is monitoring your exit node.

If a VPN were to be your exit node, then you wouldn’t be able to connect to the .onion site as it’ll see a VPN server trying to connect to it and would not be able to establish a valid socket. Tor has to be your exit node to connect to .onion sites. That would obviously require a valid Tor Client + Tor Server connection socket to establish that session. That would be like trying to plug a USB male ending into an HDMI female port.

If a VPN were to be somewhere in your connection chain, with Tor being your exit node, then you still have the same issue of that exit node being potentially compromised/owned by the government/police/etc., and the VPN would be pointless. Literally. It’s not doing anything. It is indeed an extra layer of protection as LE will have to subpoena your VPN to get the IP address of the hop before your VPN, but I discussed why most people don’t do that in my newer blog here.

You > VPN > Tor = Potential jail time or being unmasked. You > Tor > VPN = Freedom.

Remember, the VPN doesn’t offer anonymity advantages, only convenience advantage.

Let’s say hypothetically that you have a dirty exit node that belongs to the police, government, or even a malicious actor who intentionally creates exit nodes to spy on Tor users. What information can someone who owns an exit node see? They can essentially see the same data your ISP sees (when using your ISP normally without a VPN or Tor, obviously). Your Tor exit node cannot see contents of encrypted sessions (.onion sessions, HTTPS sessions, etc.), but they can see the contents of unencrypted sessions. If you use Tor to browse the clearnet and download an image over HTTP or another unencrypted network protocol, whoever owns that Tor exit node can retrieve that image. Even with encrypted sessions, the person who owns your exit node can still see the IP addresses/domains of clearnet sites that you visit, but they can’t see IP addresses/domains of .onion sites that you visit. Only your guard node (entry node) knows the .onion site you’re connecting to.

If one of the nodes in your Tor circuit are compromised, which isn’t uncommon, then your OpSec in theory should be good enough to the point where it doesn’t even matter. Anything of importance should be encrypted, and you should be manually encrypting everything that you possibly can. Are you sending an email to someone over Tor? That email should be encrypted using your PGP key. Are you attaching any files to that email? That should also be encrypted with your PGP key. Are you messaging someone on a Tor Messenger? You both should be using your PGP keys. That PGP key should be stored on, you guessed it… encrypted external media, with preferably encrypted storage containers that use a different encryption passphrase than the main/hidden volume(s).

Encrypt everything.

Crypto

Cryptocurrency is something you need to be aware of to understand security, privacy, and anonymity. It’ll come up at one point or another and you’ll benefit from having knowledge on it. This will be more apparent if you’re interested in anonymity and use the Dark web a lot. You’ll see it plenty there. This will be by no means a “get your PHD in crypto” section.

The main thing you need to understand is that most cryptocurrencies are not anonymous by default unless if used properly. Bitcoin is a great example and is the one many immediately think of as it’s the staple of crypto. All Bitcoin transactions are publicly available for anyone to see, which could be breadcrumbs to help identify patterns that could ultimately lead to your identity being unmasked. We’ll cover more on this later, but for now we’ll save this for later.

I first recommend that you learn about what crypto is as a whole prior to learning about individual cryptocurrencies (bitcoin, etc.). I’ll link some videos to get you started. Feel free to do your own research to fill in any voids not covered in the videos.

How Cryptocurrency ACTUALLY works:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYQgy8QDEBI

Explain Crypto To COMPLETE Beginners: My Guide!!:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VYWc9dFqROI&t

Do you understand what crypto is yet? Great. We can move on to individual cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin, ethereum, monero, etc.

There’s hundreds of different cryptocurrencies. Don’t let that scare you. There’s only a handful of big ones, many are shitcoins that people try to create (anyone can create a cryptocurrency). I will leave it up to you to learn about the ones you’re interested in. You need to remember that although they all share one thing in common: they are all cryptocurrencies, they are also different in terms of how they function. Essentially, a coin gains traction, its value increases, and eventually it becomes mainstream to the point where services we all know and love offer them as a method of payment. Sure, you may own a lot of “Speedy Coin”!! (made that up) But nobody knows what the fuck speedy coin is and it isn’t a valued crypto. Nobody is going to accept payment in that coin. Don’t pay attention to coins that aren’t popular, unless you’re trying to make your own or promote/support a smaller coin, etc.

Bitcoin isn’t very convenient for privacy by default, whereas a coin such as Monero is designed to be more private. These are things that are important to know. Crypto can have a huge learning curve so don’t worry if you walk away without learning much of value. You’ll get it over time.

Fortunately for you, you’re just learning the basics. For privacy, anonymity, and OPSEC, the main thing that you need to know is that many cryptocurrencies have a public block chain that logs every transaction tied to that crytocurrency’s wallet that anyone at anytime can view. Think of a Bitcoin wallet as your bank account statement being publicly accessible. Anyone can see the amount of bitcoin that you’re sending and receiving, as well as the bitcoin addresses you’re sending and receiving from. Bitcoin is the best example of this and you will likely get caught if you buy illegal things with bitcoin (or tie them to your illegal activities) without taking the proper steps to obfuscate the payments or if you’re using coins that you didn’t obtain anonymously.

Bitcoin mixers are quite common and is what many people use to help obfuscate their bitcoin transactions. Think of a bitcoin mixer as a hat. You will “put your bitcoin into a hat” with other peoples bitcoin. The hat will then shake itself and mix the coins. The mixer will randomly spit the bitcoin into random “pools” that will then be sent back to your dedicated “mixing” bitcoin address. You should theoritically have a dedicated bitcoin address that you use solely for retrieving mixed bitcoin for obvious OpSec reasons.

Getting your first batch of crypto is the hard part. I know it’s tempting to simply register at an exhange such as Coinbase and then buy Bitcoin using your Credit Card, but that isn’t a good idea for VERY obvious reasons. These exchanges also require you to verify your ID, BTW.

How do you obtain your first batch of crypto anonymously? There are many ways. Just like everything in life, there are legal and not so legal ways of doing it. The legal ways could be setting up a miner and then routing it through Tor, you can earn the crypto by doing work for someone in return for crypto, or you can even utilize websites online that allow you to meet with people local to you to exhange bitcoin for cash (I personally wouldn’t recommend but you do you).

The not so legal ways may include creating crypto miner malware, with another example being malware that simply steals bitcoin address information. There’s even malware out there disguised as Crypto wallet apps (for example) that phishes you into giving them crypto or your wallet information. The list goes on and on;

extortion, you name it. Keep in mind that no illegal activities mentioned are encouraged, they are mentioned to inform you of their existence.

Part III

Most of the content that I am planning on adding to part III will likely be added as their own blog posts, instead of being shoved into an all-in-one “security thread”. The reason for this change likely occuring is due to the time and planning it takes to plan, write, and publish these lengthy threads. It’s much more enjoyable for me to post various blog posts about topics xyz than it is to condense them all into a “security thread”.

After all, every post on my blog is related to security, privacy, anonymity, OpSec, OSINT, etc.. It doesn’t really matter one way or the other.